MIT engineers report today that they have cooked up a material that is 10 times blacker than anything that has previously been reported. The material is made from vertically aligned carbon nanotubes, or CNTs — microscopic filaments of carbon, like a fuzzy forest of tiny trees, that the team grew on a surface of chlorine-etched aluminum foil. The foil captures at least 99.995 percent* of any incoming light, making it the blackest material on record. (from news.mit.edu)

The researchers have published their findings today in the journal ACS-Applied Materials and Interfaces. They are also showcasing the cloak-like material as part of a new exhibit today at the New York Stock Exchange, titled “The Redemption of Vanity.”

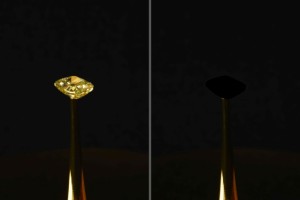

The artwork, a collaboration between Brian Wardle, professor of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT, and his group, and MIT Center for Art, Science, and Technology artist-in-residence Diemut Strebe, features a 16.78-carat natural yellow diamond from LJ West Diamonds, estimated to be worth $2 million, which the team coated with the new, ultrablack CNT material. The effect is arresting: The gem, normally brilliantly faceted, appears as a flat, black void.

Wardle says the CNT material, aside from making an artistic statement, may also be of practical use, for instance in optical blinders that reduce unwanted glare, to help space telescopes spot orbiting exoplanets.

Wardle says the CNT material, aside from making an artistic statement, may also be of practical use, for instance in optical blinders that reduce unwanted glare, to help space telescopes spot orbiting exoplanets.

“There are optical and space science applications for very black materials, and of course, artists have been interested in black, going back well before the Renaissance,” Wardle says. “Our material is 10 times blacker than anything that’s ever been reported, but I think the blackest black is a constantly moving target. Someone will find a blacker material, and eventually we’ll understand all the underlying mechanisms, and will be able to properly engineer the ultimate black.”

Wardle’s co-author on the paper is former MIT postdoc Kehang Cui, now a professor at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Into the void

Wardle and Cui didn’t intend to engineer an ultrablack material. Instead, they were experimenting with ways to grow carbon nanotubes on electrically conducting materials such as aluminum, to boost their electrical and thermal properties.

But in attempting to grow CNTs on aluminum, Cui ran up against a barrier, literally: an ever-present layer of oxide that coats aluminum when it is exposed to air. This oxide layer acts as an insulator, blocking rather than conducting electricity and heat. As he cast about for ways to remove aluminum’s oxide layer, Cui found a solution in salt, or sodium chloride.

At the time, Wardle’s group was using salt and other pantry products, such as baking soda and detergent, to grow carbon nanotubes. In their tests with salt, Cui noticed that chloride ions were eating away at aluminum’s surface and dissolving its oxide layer.

“This etching process is common for many metals,” Cui says. “For instance, ships suffer from corrosion of chlorine-based ocean water. Now we’re using this process to our advantage.”

Cui found that if he soaked aluminum foil in saltwater, he could remove the oxide layer. He then transferred the foil to an oxygen-free environment to prevent reoxidation, and finally, placed the etched aluminum in an oven, where the group carried out techniques to grow carbon nanotubes via a process called chemical vapor deposition.

By removing the oxide layer, the researchers were able to grow carbon nanotubes on aluminum, at much lower temperatures than they otherwise would, by about 100 degrees Celsius. They also saw that the combination of CNTs on aluminum significantly enhanced the material’s thermal and electrical properties — a finding that they expected.

What surprised them was the material’s color.

“I remember noticing how black it was before growing carbon nanotubes on it, and then after growth, it looked even darker,” Cui recalls. “So I thought I should measure the optical reflectance of the sample.

“Our group does not usually focus on optical properties of materials, but this work was going on at the same time as our art-science collaborations with Diemut, so art influenced science in this case,” says Wardle.

Wardle and Cui, who have applied for a patent on the technology, are making the new CNT process freely available to any artist to use for a noncommercial art project.

“Built to take abuse”

Cui measured the amount of light reflected by the material, not just from directly overhead, but also from every other possible angle. The results showed that the material absorbed at least 99.995 percent of incoming light, from every angle. In other words, it reflected 10 times less light than all other superblack materials, including Vantablack. If the material contained bumps or ridges, or features of any kind, no matter what angle it was viewed from, these features would be invisible, obscured in a void of black.

The researchers aren’t entirely sure of the mechanism contributing to the material’s opacity, but they suspect that it may have something to do with the combination of etched aluminum, which is somewhat blackened, with the carbon nanotubes. Scientists believe that forests of carbon nanotubes can trap and convert most incoming light to heat, reflecting very little of it back out as light, thereby giving CNTs a particularly black shade.

“CNT forests of different varieties are known to be extremely black, but there is a lack of mechanistic understanding as to why this material is the blackest. That needs further study,” Wardle says.

The material is already gaining interest in the aerospace community. Astrophysicist and Nobel laureate John Mather, who was not involved in the research, is exploring the possibility of using Wardle’s material as the basis for a star shade — a massive black shade that would shield a space telescope from stray light.

“Optical instruments like cameras and telescopes have to get rid of unwanted glare, so you can see what you want to see,” Mather says. “Would you like to see an Earth orbiting another star? We need something very black. … And this black has to be tough to withstand a rocket launch. Old versions were fragile forests of fur, but these are more like pot scrubbers — built to take abuse.”

*An earlier version of this story stated that the new material captures more than 99.96 percent of incoming light. That number has been updated to be more precise; the material absorbs at least 99.995 of incoming light.